In 1952, Stanley Miller and Harold Urey carried out a chemical experiment to demonstrate how organic molecules could have formed spontaneously from inorganic precursors under prebiotic conditions like those posited by the Oparin�Haldane hypothesis. It used a highly reducing (lacking oxygen) mixture of gases�methane, ammonia, and hydrogen, as well as water vapor�to form simple organic monomers such as amino acids. Bernal said of the Miller�Urey experiment that "it is not enough to explain the formation of such molecules, what is necessary, is a physical-chemical explanation of the origins of these molecules that suggests the presence of suitable sources and sinks for free energy. However, current scientific consensus describes the primitive atmosphere as weakly reducing or neutral, diminishing the amount and variety of amino acids that could be produced. The addition of iron and carbonate minerals, present in early oceans, however produces a diverse array of amino acids. Later work has focused on two other potential reducing environments: outer space and deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

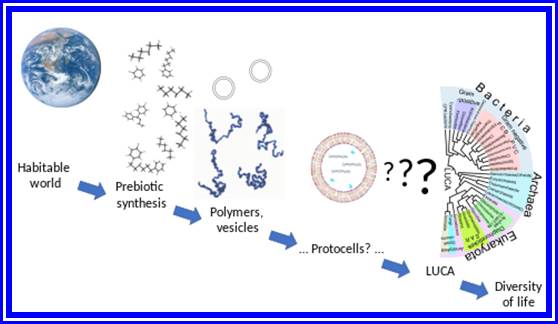

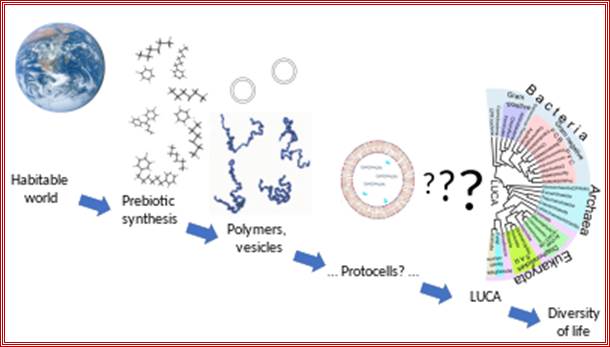

Stages in the origin of life range from the well-understood, such as the habitable Earth and the abiotic synthesis of simple molecules, to the largely unknown, like the derivation of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) with its complex molecular functionalities.[1]

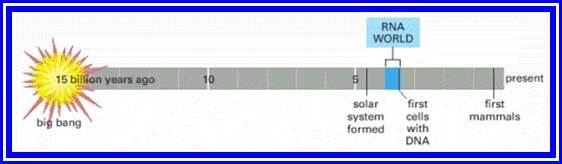

Life first- emerged at least 3.8 billion years ago (?), approximately 750 million years after Earth was formed (Figure above). How life originated and how the first cell came into being are matters of speculation, since these events cannot be reproduced in the laboratory.

Early universe with first stars:

Soon after the Big Bang, which occurred roughly 14 GA, (A= Billion years or Giga-annum (109 years), the only chemical elements present in the universe were Hydrogen, Helium, and Lithium, the three lightest atoms in the periodic table. These elements gradually came together to form stars. These early stars were massive and short-lived, producing all the heavier elements through stellar nucleosynthesis. Carbon, currently the fourth most abundant chemical elements in the universe (after hydrogen, helium and oxygen), was formed mainly in white dwarf stars, particularly those bigger than twice the mass of the sun. As these stars reached the end of their lifecycles, they ejected these heavier elements, among them carbon and oxygen, throughout the universe. These heavier elements allowed for the formation of new objects, including rocky planets and other bodies. According to the nebular hypothesis, the formation and evolution of the Solar System began 4.6 GA with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into a protoplanetary disk out of which the planets, moons, asteroids, and other small Solar System bodies formed.

The Earth was formed 4.54 GA. The Hadean Earth (from its formation until 4 GA) was at first inhospitable to any living organisms. During its formation, the Earth lost a significant part of its initial mass, and consequentially lacked the gravity to hold molecular hydrogen and the bulk of the original inert gases. The atmosphere consisted largely of water vapor, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide, with smaller amounts of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and sulfur compounds.[55] The solution of carbon dioxide in water is thought to have made the seas slightly acidic, with a pH of about 5.5. The Hadean atmosphere has been characterized as a "gigantic, productive outdoor chemical laboratory, similar to volcanic gases today which still support some abiotic chemistry. Earliest evidence of life.

Main article: Earliest known life forms

Life existed on Earth more than 3.5 GA, during the Eoarchean when sufficient crust had solidified following the molten Hadean. The earliest physical evidence of life so far found consists of microfossils in the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt of Northern Quebec, in banded iron formation rocks at least 3.77 and possibly 4.28 GA. The micro-organisms lived within hydrothermal vent precipitates, soon after the 4.4 GA formation of oceans during the Hadean. The microbes resembled modern hydrothermal vent bacteria, supporting the view that abiogenesis began in such an environment.

Biogenic graphite has been found in 3.7 GA metasedimentary rocks from southwestern Greenland and in microbial mat fossils from 3.49 GA Western Australian sandstone. Evidence of early life in rocks from Akilia Island, near the Isua supracrustal belt in southwestern Greenland, dating to 3.7 GA, have shown biogenic carbon isotopes.[78] In other parts of the Isua supracrustal belt, graphite inclusions trapped within garnet crystals are connected to the other elements of life: oxygen, nitrogen, and possibly phosphorus in the form of phosphate, providing further evidence for life 3.7 GA. In the Pilbara region of Western Australia, compelling evidence of early life was found in pyrite-bearing sandstone in a fossilized beach, with rounded tubular cells that oxidized sulfur by photosynthesis in the absence of oxygen. Zircons from Western Australia imply that life existed on Earth at least 4.1 GA years back , GA means 109 yrs. The Pilbara region of Western Australia contains the Dresser Formation with rocks 3.48 GA, including layered structures called stromatolites. Their modern counterparts are created by photosynthetic micro-organisms including cyanobacteria.[83] These lie within undeformed hydrothermal-sedimentary strata; their texture indicates a biogenic origin. Parts of the Dresser formation preserve hot springs on land, but other regions seem to have been shallow seas.

Stromatolites in the Siyeh Formation, Glacier National Park, dated 3.5 GA, placing them among the earliest life-forms

Modern stromatolites in Shark Bay, created by photosynthetic cyanobacteria.

All chemical elements except for hydrogen and helium derive from stellar nucleosynthesis. The basic chemical ingredients of life � the carbon-hydrogen molecule (CH), the carbon-hydrogen positive ion (CH+) and the carbon ion (C+) � were produced by ultraviolet light from stars.[85] Complex molecules, including organic molecules, form naturally both in space and on planets.[86] Organic molecules on the early Earth could have had either terrestrial origins, with organic molecule synthesis driven by impact shocks or by other energy sources, such as ultraviolet light, redox coupling, or electrical discharges; or extraterrestrial origins (pseudo-panspermia), with organic molecules formed in interstellar dust clouds raining down on to the planet.

Nucleobases.

The majority of organic compounds introduced on Earth by interstellar dust particles have helped to form complex molecules, thanks to their peculiar surface-catalytic activities. Studies of the 12C/13C -isotopic ratios of organic compounds in the Murchison meteorite suggest that the RNA component uracil and related molecules, including xanthine, were formed extra terrestrially. NASA studies of meteorites suggest that all four DNA nucleobases (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) have been formed in outer space. The cosmic dust permeating the universe contains complex organics ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic�aliphatic structure") that could be created rapidly by stars. Glycolaldehyde, a sugar molecule and RNA precursor, has been detected in regions of space including around protostars and on meteorites.

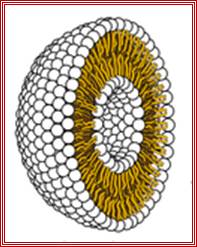

The lipid world theory postulates that the first self-replicating object was lipid-like. Phospholipids form lipid bilayers in water while under agitation�the same structure as in cell membranes. These molecules were not present on early Earth, but other amphiphilic long-chain molecules also form membranes. These bodies may expand by insertion of additional lipids, and may spontaneously split into two offspring of similar size and composition. The main idea is that the molecular composition of the lipid bodies is a preliminary to information storage, and that evolution led to the appearance of polymers like RNA that store information. Studies on vesicles from amphiphiles that might have existed in the prebiotic world have so far been limited to systems of one or two types of amphiphiles.

A lipid bilayer membrane could be composed of a huge number of combinations of arrangements of amphiphiles. The best of these would have favored the constitution of a hypercycle, actually a positive feedback composed of two mutual catalysts represented by a membrane site and a specific compound trapped in the vesicle. Such site/compound pairs are transmissible to the daughter vesicles leading to the emergence of distinct lineages of vesicles, which would have allowed natural selection.

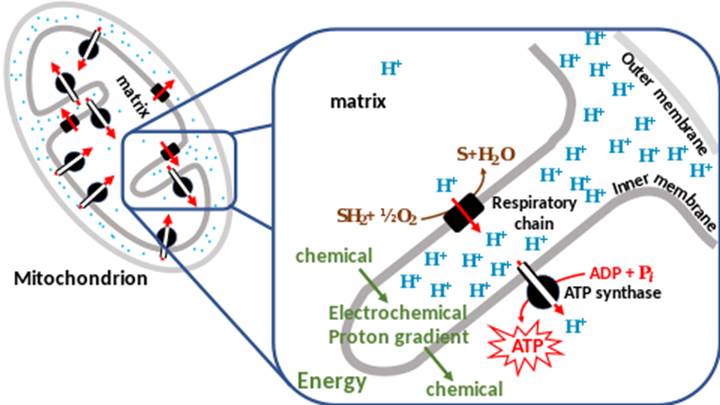

Chemiosmosis.

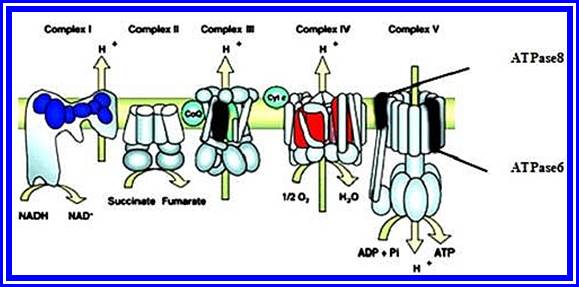

ATP synthase uses the chemiosmotic proton gradient to power ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation.

In 1961, Peter Mitchell proposed chemiosmosis as a cell's primary system of energy conversion. The mechanism, now ubiquitous in living cells, powers energy conversion in micro-organisms and in the mitochondria of eukaryotes, making it a likely candidate for early life.[149][150] Mitochondria produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of the cell used to drive cellular processes such as chemical syntheses. The mechanism of ATP synthesis involves a closed membrane in which the ATP synthase enzyme is embedded. The energy required to release strongly-bound ATP has its origin in protons that move across the membrane. In modern cells, those proton movements are caused by the pumping of ions across the membrane, maintaining an electrochemical gradient. In the first organisms, the gradient could have been provided by the difference in chemical composition between the flow from a hydrothermal vent and the surrounding seawater or perhaps meteoric quinones that were conducive to the development of chemiosmotic energy across lipid membranes if at a terrestrial origin.

Chemiosmotic coupling in the membranes of a mitochondrion

The RNA world.

Main article: RNA world.

The RNA world hypothesis describes an early Earth formation of self-replicating and catalytic RNA and not DNA or proteins. Many researchers concur that an RNA world must have preceded the DNA-based life that now dominates. However, RNA-based life may not have been the first to exist. Another model echoes Darwin's "warm little pond" with cycles of wetting and drying. �

RNA is central to the translation process. Small RNAs can catalyze all the chemical groups and information transfers required for life. RNA both expresses and maintains genetic information in modern organisms; and the chemical components of RNA are easily synthesized under the conditions that approximated the early Earth, which were very different from those that prevail today. The structure of the ribozyme has been called the "smoking gun", with a central core of RNA and no amino acid side chains within 18 � of the active site that catalyzes peptide bond formation.

The concept of the RNA world was proposed in 1962 by Alexander Rich, and the term was coined by Walter Gilbert in 1986. There were initial difficulties in the explanation of the abiotic synthesis of the nucleotides cytosine and uracil. Subsequent research has shown possible routes of synthesis; for example, formamide produces all four ribonucleotides and other biological molecules when warmed in the presence of various terrestrial minerals.

The RNA world hypothesis proposes that undirected polymerization led to the emergence of ribozymes, and in turn to an RNA replicase.

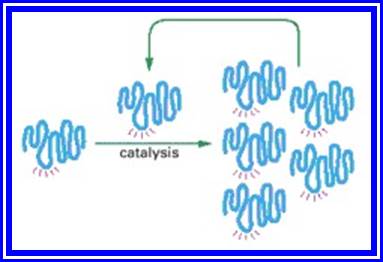

RNA replicase can function as both coded and catalyst for further RNA replication, i.e. it can be autocatalytic. Jack Szostak has shown that certain catalytic RNAs can join smaller RNA sequences together, creating the potential for self-replication. The RNA replication systems, which include two ribozymes that catalyze each other's synthesis, showed a doubling time of the product of about one hour, and were subject to natural selection under the experimental conditions. If such conditions were present on early Earth, then natural selection would favor the proliferation of such autocatalytic sets, to which further functionalities could be added. Self-assembly of RNA may occur spontaneously in hydrothermal vents. A preliminary form of tRNA could have assembled into such a replicator molecule.

Possible precursors to protein synthesis include the synthesis of short peptide cofactors or the self-catalyzing duplication of RNA. It is likely that the ancestral ribosome was composed entirely of RNA, although some roles have since been taken over by proteins. Major remaining questions on this topic include identifying the selective force for the evolution of the ribosome and determining how the genetic code arose.

Eugene Koonin has argued that "no compelling scenarios currently exist for the origin of replication and translation, the key processes that together comprise the core of biological systems and the apparent pre-requisite of biological evolution. The RNA World concept might offer the best chance for the resolution of this conundrum but so far cannot adequately account for the emergence of an efficient RNA replicase or the translation system."

Phylogeny and LUCA[edit]

Further information: Last universal common ancestor.

Starting with the work of Carl Woes from 1977 onwards, genomics studies have placed the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of all modern life-forms between Bacteria and a clade formed by Archaea and Eukaryota in the phylogenetic tree of life. It lived over 4 Gya. A minority of studies have placed the LUCA in Bacteria, proposing that Archaea and Eukaryota are evolutionarily derived from within Eubacteria; Thomas Cavalier-Smith suggested that the phenotypically diverse bacterial phylum Chloroflexota contained the LUCA. �

Phylogeny and LUCA.

Further information: Last universal common ancestor

Starting with the work of Carl Woes from 1977 onwards, genomics studies have placed the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all modern life-forms between Bacteria and a clade formed by Archaea and Eukaryote in the phylogenetic tree of life. It lived over 4 GA. A minority of studies have placed the LUCA in Bacteria, proposing that Archaea and Eukaryota are evolutionarily derived from within Eubacteria; Thomas Cavalier-Smith suggested that the phenotypically diverse bacterial phylum Chloroflexota contained the LUCA. �

Phylogenetic tree above showing the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) at the root. The major clades are the Bacteria on one hand, and the Archaea and Eukaryota on the other.

In 2016, a set of 355 genes likely present in the LUCA was identified. A total of 6.1 million prokaryotic genes from Bacteria and Archaea were sequenced, identifying 355 protein clusters from amongst 286,514 protein clusters that were probably common to the LUCA. The results suggest that the LUCA was anaerobic with a Wood�Ljungdahl pathway, nitrogen- and carbon-fixing, thermophilic. Its cofactors suggest dependence upon an environment rich in hydrogen, carbon dioxide, iron, and transition metals. Its genetic material was probably DNA, requiring the 4-nucleotide genetic code, messenger RNA, transfer RNAs, and ribosomes to translate the code into proteins such as enzymes. LUCA likely inhabited an anaerobic hydrothermal vent setting in a geochemically active environment. It was evidently already a complex organism, and must have had precursors; it was not the first living thing. The physiology of LUCA has been in dispute. �

Leslie Orgel argued that early translation machinery for the genetic code would be susceptible to error catastrophe. Geoffrey Hoffmann however showed that such machinery can be stable in function against "Orgel's paradox". �

Water- single celled life:

We may never be able to prove beyond any doubt how life first evolved. But of the many explanations proposed, one stands out � the idea that life evolved in hydrothermal vents deep under the sea. Not in the superhot black smokers, but more placid affairs known as alkaline hydrothermal vents.

This theory can explain life�s strangest feature, and there is growing evidence to support it.

Earlier this year, for instance, lab experiments confirmed that conditions in some of the numerous pores within the vents can lead to high concentrations of large molecules. This makes the vents an ideal setting for the �RNA world� widely thought to have preceded the first cells.

If life did evolve in alkaline hydrothermal vents, it might have happened something like this:

1.

Water percolated down into newly formed rock under the seafloor, where it reacted with minerals such as olivine, producing a warm alkaline fluid rich in hydrogen, sulphides and other chemicals � a process called �serpentinization�.

This hot fluid welled up at alkaline hydrothermal vents like those at the Lost City, a vent system discovered near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in 2000.

2.

Unlike today�s seas, the early ocean was acidic and rich in dissolved iron. When upwelling hydrothermal fluids reacted with this primordial seawater, they produced carbonate rocks riddled with tiny pores and a �foam� of iron-Sulphur bubbles.

3.

Inside the iron-Sulphur bubbles, hydrogen reacted with carbon dioxide, forming simple organic molecules such as methane, formate and acetate. Some of these reactions were catalyzed by the iron-Sulphur minerals. Similar iron-Sulphur catalysts are still found at the heart of many proteins today.

4.

The electrochemical gradient between the alkaline vent fluid and the acidic seawater leads to the spontaneous formation of acetyl phosphate and pyrophosphate, which act just like adenosine triphosphate or ATP, the chemical that powers living cells.

These molecules drove to the formation of amino acids � the building blocks of proteins � and nucleotides-the building blocks for RNA and DNA.

5.

Thermal currents and diffusion within the vent pores concentrated larger molecules like nucleotides, driving the formation of RNA and DNA � and providing an ideal setting for their evolution into the world of DNA and proteins. Evolution got under way, with sets of molecules capable of producing more of themselves starting to dominate.

6.

Fatty molecules coated the iron-Sulphur froth and spontaneously formed cell-like bubbles. Some of these bubbles would have enclosed self-replicating sets of molecules � the first organic cells. The earliest protocells may have been elusive entities, though, often dissolving and reforming as they circulated within the vents.

7.

The evolution of an enzyme called pyrophosphatase, which catalyzes the production of pyrophosphate, allowed the protocells to extract more energy from the gradient between the alkaline vent fluid and the acidic ocean. This ancient enzyme is still found in many bacteria and archaea, the first two branches on the tree of life.

8.

Some protocells started using ATP as well as acetyl phosphate and pyrophosphate. The production of ATP using energy from the electrochemical gradient is perfected with the evolution of the enzyme ATP synthase, found within all life today.

9.

Protocells further from the main vent axis, where the natural electrochemical gradient is weaker, started to generate their own gradient by pumping protons across their membranes, using the energy released when carbon dioxide reacts with hydrogen.

This reaction yields only a small amount of energy, not enough to make ATP. By repeating the reaction and storing the energy in the form of an electrochemical gradient, however, protocells �saved up� enough energy for ATP production.

10.

Once protocells could generate their own electrochemical gradient, they were no longer tied to the vents. Cells left the vents on two separate occasions, with one exodus giving rise to bacteria and the other to archaea.

Back to feature: Was our oldest ancestor a proton-powered rock? New scientist. �https://www.newscientist.com/

What was needed for the first cell? Some sort of membrane surrounding organic molecules? Probably.

How, organic molecules such as RNA developed into cells is not known for certain. Scientists speculate that lipid membranes grew around the organic molecules. The membranes prevented the molecules from reacting with other molecules, so they did not form new compounds. In this way, the organic molecules persisted, and the first cells may have formed.� Figure below shows a model of the hypothetical first cell. Were these first cells the first living organisms? Were they able to live and reproduce while passing their genetic information to the next generation? If so, then yes, these first cells could be considered the first living organisms.

Hypothetical First Cell. The earliest cells may have consisted of little more than RNA inside a lipid membrane.

LUCA.

No doubt there were many early cells of this type. However, scientists think that only one early cell (or group of cells) eventually gave rise to all subsequent life on Earth. That one cell is called the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). It probably existed around 3.5 billion years ago. LUCA was one of the earliest prokaryotic cells. It would have lacked a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. To learn more about LUCA and universal common descent, you can watch the video at the following link: http:// www.youtube.com/watch? v=G0UGpcea8Zg.

� The first cells consisted of little more than an organic molecule such as RNA inside a lipid membrane.

� One cell (or group of cells), called the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), gave rise to all subsequent life on Earth.

� Photosynthesis evolved by 3 billion years ago and released oxygen into the atmosphere.

� Cellular respiration evolved after that to make use of the oxygen.

LUCA

No doubt there were many early cells of this type. However, scientists think that only one early cell (or group of cells) eventually gave rise to all subsequent life on Earth. That one cell is called the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). It probably existed around 3.5 billion years ago. LUCA was one of the earliest prokaryotic cells. It would have lacked a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. To learn more about LUCA and universal common descent, you can watch the video at the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0UGpcea8Zg.

Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration;

The earliest cells were probably heterotrophs. Most likely they got their energy from other molecules in that time �organic-soup.� However, by about 3 billion years ago, a new way of obtaining energy evolved. This new way was photosynthesis. Through photosynthesis, organisms could use sunlight to make food from carbon dioxide and water. These organisms were the first autotrophs. They provided food for themselves and for other organisms that began to consume them.

After photosynthesis evolved, oxygen started to accumulate in the atmosphere. This has been dubbed the �oxygen catastrophe.� Why? Oxygen was toxic to most early cells because they had evolved in its absence. As a result, many of them died out. The few that survived evolved a new way to take advantage of the oxygen. This second major innovation was cellular respiration. It allowed cells to use oxygen to obtain more energy from organic molecules.

Summary

� The first cells consisted of little more than an organic molecule such as RNA inside a lipid membrane.

� One cell (or group of cells), called the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), gave rise to all subsequent life on Earth.

� Photosynthesis evolved by 3 billion years ago and released oxygen into the atmosphere.

� Cellular respiration evolved after that to make use of the oxygen.

Formation life molecules- many-many million years since the origin of earth- production life required molecules and association of them using membrane forms; more than anything life as a molecular form coordinating from each other and heritable-it has molecular origin. that is the fundamental; to function the life molecule requires DNA and RNA and importantly polypeptide molecules and lipid molecules to enclose them all in one area.

The history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geological change and biological evolution.� �������������

����������������������������������� �����������

Early life may have emerged from a mixture of RNA and DNA building blocks, developing the two nucleic acids simultaneously instead of evolving DNA from RNA.https://www.scientificamerican.com/

����������� As RNA gave way to DNA, some think a mixture of nucleotide building blocks would have been inevitable. As these nucleotides connected to form strands, the thermodynamic and kinetic stability of pure RNA and DNA duplexes would drive these nucleic acids to accumulate in primitive cells, while less thermally stable complexes containing one strand of RNA and one strand of DNA fell apart.

Research in different fields is coming together to assemble a more complete picture of the way the RNA World began and operated. ������������� https://www.nature.com/

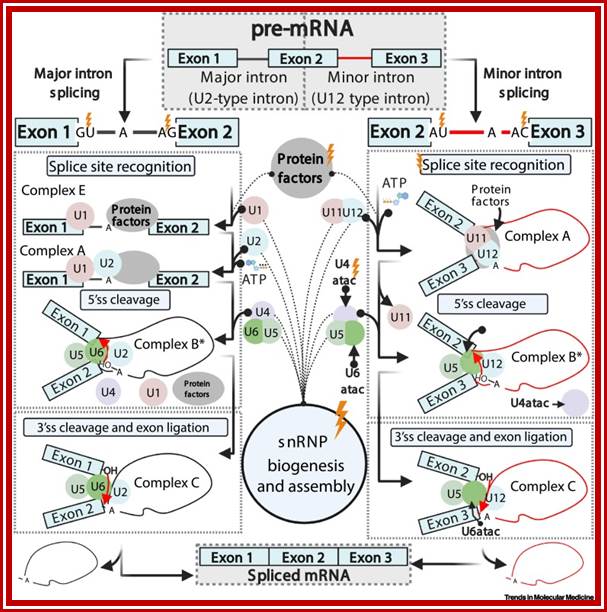

Minor and Major Spliceosome Assembly and Catalytic Core Formation.

https://www.cell.com/

Figure; An RNA molecule that can catalyze its own synthesis

Figure; An RNA molecule that can catalyze its own synthesis

This hypothetical process would require catalysis of the production of both a second RNA strand of complementary nucleotide sequence and the use of this second RNA molecule as a template to form many molecules of RNA with the original sequence. The red rays represent the active site of this hypothetical RNA enzyme.

�����������������������������������������������������������

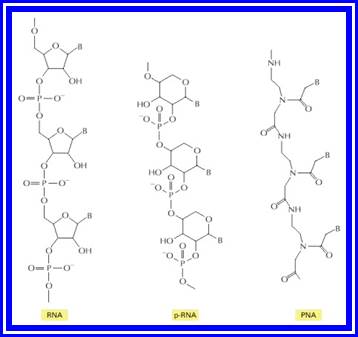

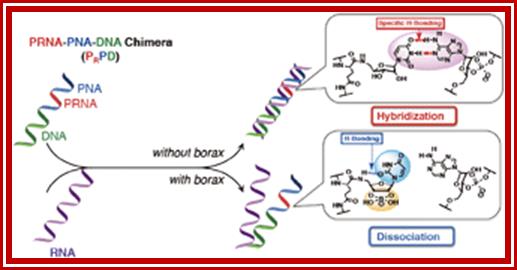

Figure: Structures of RNA from the left and two related information-carrying polymers;� pRNA, and PNA;

In each case, B indicates the positions of purine and pyrimidine bases. The polymer p-RNA (pyranosyl-RNA) is RNA in which the furanose (five-membered ring) form of ribose has been replaced by the pyranose (six-membered ring) form. In PNA (peptide nucleic acid), the ribose phosphate backbone of RNA has been replaced by the peptide backbone found in proteins. Like RNA, both p-RNA and PNA can form double helices through complementary base-pairing, and each could therefore in principle serve as a template for its own synthesis.�������������� �����������������������������������

Early life may have emerged from a mixture of RNA and DNA building blocks, developing the two nucleic acids simultaneously instead of evolving DNA from RNA.

Employing the module strategy based on our recent finding that the recognition behavior of peptide ribonucleic acid (PRNA) with complementary DNA/RNA is effectively controlled by the anti-to-syn orientation switching of pyrimidine nucleobase induced by borate ester formation, we designed and synthesized PRNA�DNA and PRNA�PNA�DNA chimeras. In these chimeras, both of the PRNA (or PRNA�PNA) and DNA domains recognize the complementary DNA/RNA to form a stable complex, and the PRNA domain is simultaneously expected to play the dual role of switching the recognition behavior and inhibiting hydrolysis by exonucleases. The complexation and recognition control behaviors of these chimeras with DNA and RNA have been elucidated. https://www.journal.csj.jp/

�����������������������������������������������������������������������

Beginning with a large pool of nucleic acid molecules synthesized in the laboratory, those rare RNA molecules that possess a specified catalytic activity can be isolated and studied. Although a specific example (that of an auto-phosphorylating -ribozyme) is shown, variations of this procedure have been used to generate many of the ribozymes listed. During the autophosphorylation step, the RNA molecules are sufficiently dilute to prevent the �cross�-phosphorylation of additional RNA molecules. In reality, several repetitions of this procedure are necessary to select the very rare RNA molecules with catalytic activity. Thus the material initially eluted from the column is converted back into DNA, amplified many fold (using reverse transcriptase and PCR as explained in Chapter 8), transcribed back into RNA, and subjected to repeated rounds of selection. (Adapted from J.R. Lorsch and J.W. Szostak, Nature 371:31�36, 1994.)

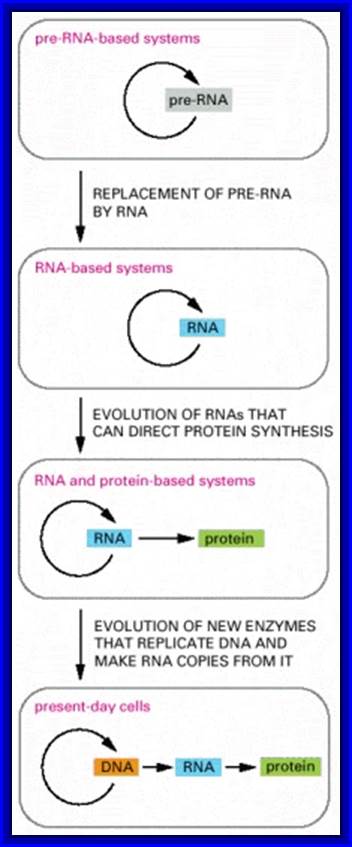

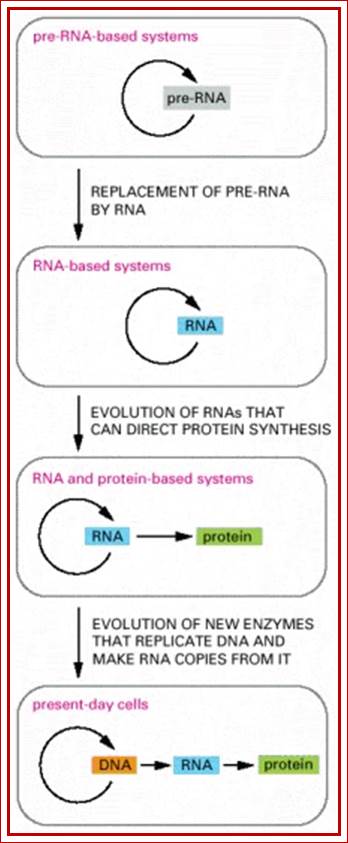

From our knowledge of present-day organisms and the molecules they contain, it seems likely that the development of the directly autocatalytic mechanisms fundamental to living systems began with the evolution of families of molecules that could catalyze their own replication. With time, a family of cooperating RNA catalysts probably developed the ability to direct synthesis of polypeptides. DNA is likely to have been a late addition: as the accumulation of additional protein catalysts allowed more efficient and complex cells to evolve, the DNA double helix replaced RNA as a more stable molecule for storing the increased amounts of genetic information required by such cells.

Figure- above. The hypothesis that RNA preceded DNA and proteins in evolution;

In the earliest cells, pre-RNA molecules would have had combined genetic, structural, and catalytic functions and these functions would have gradually been replaced by RNA. In present-day cells, DNA is the repository of genetic information, and proteins perform the vast majority of catalytic functions in cells. RNA primarily functions today as a go-between in protein synthesis, although it remains a catalyst for a number of crucial reactions.

Fig; RNA to RNA; RNA to Proteins, DNA to RNA to Proteins; where is RNA to DNA to RNA?

Figure: The hypothesis that RNA preceded DNA and proteins in evolution.

In the earliest cells, Pre-RNA molecules would have had combined genetic, structural, and catalytic functions and these functions would have gradually been replaced by DNA. In present-day cells, DNA is the repository of genetic information, and proteins perform the vast majority of catalytic functions in cells. RNA primarily functions today as a go-between in protein synthesis, although it remains a catalyst for a number of crucial reactions.

Scientists find that an RNA-DNA mix may have created the first life on our planet. DNA model being created. New study shows that RNA and DNA likely originated together? The mixture of the acids is believed to have produced Earth's first life forms.

Experts now think that Miller and Urey�s experiments didn�t get the atmosphere of early Earth quite right, but more recent experiments have shown that organic building blocks, including nucleotides, can form under a relatively wide range of conditions that could have been present on the primordial earth.

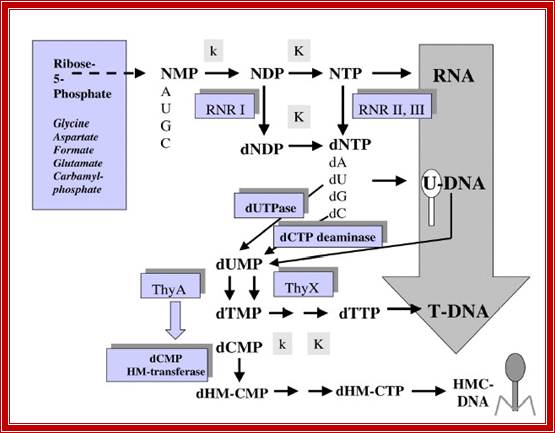

����������������������� Pathways for the synthesis of RNA and DNA

Figure (above).

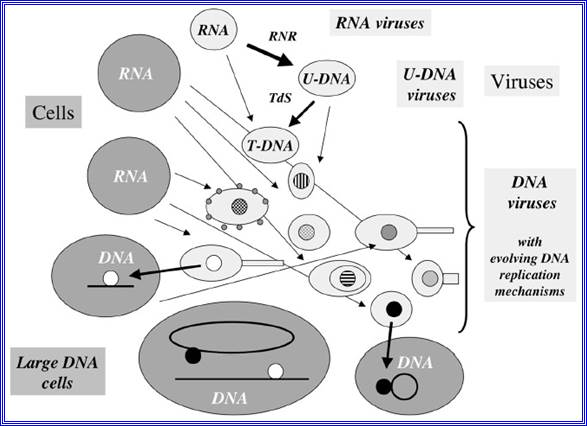

Metabolic pathways for RNA and DNA precursors biosynthesis: a palimpsest from the RNA to DNA world transition? The biosynthetic pathways for purine and pyrimidine nucleotides both start with ribose 5-monophosphate. The formation of the four bases requires several amino-acids, formate and carbamoyl-phosphate. Nucleotide monophosphates (NMP) are converted into RNA precursors (NTP) by NMP kinases (k) and NDP kinases (K). These reactions probably are relics of the RNA-protein world. DNA precursors are produced from NDP and/or NTP by ribonucleotide reductases (RNR), except for dTTP, which results from methylation of dUMP. dTMP is produced from dUMP by Thymidylate synthases (ThyA or ThyX) and converted into dTTP by the same kinases that convert NMP into NTP. dUMP can be produced either by dUTPAse or by dCTP deaminase. In the U-DNA world, it could have been also produced by degradation of U-DNA. The mode of dTMP production clearly suggests that U-DNA was an evolutionary intermediate between RNA and T-DNA. Some viruses contain U-DNA, whereas others contain HMC-DNA (HMC= hydroxymethyl-cytosine). Transformation of C into HMC occurs at the level of dCMP, and conversion of dCMP into dHMCMP is catalyzed by a dCMP hydroxy-methyl transferase (dCMP HM transferase), which is homologue to ThyA (See refs. 11, 14, and 19 for more details).

RNA to DNA

Figure- above:

Evolution of DNA replication mechanisms in the viral world? This figure illustrates a coevolution scenario of cells and viruses in the transition from the RNA to the DNA world. Large gray circles or ovals indicate cells, whereas small light grey circles ovals (some with tails) indicate viruses. In this scenario, different replication mechanisms (inner circles with different colors) originated among various viral lineages after the invention of U-DNA and T-DNA by viruses (RNR= ribonucleotide reductase, TdS=Thymidylate synthase).7 These mechanisms evolved through the independent recruitment of cellular or viral enzymes involved in RNA replication or transcription (polymerases, helicases, nucleotide binding proteins) to produce enzymes involved in DNA replication (thin arrows). Two different DNA replication mechanisms (black and white circles) were finally transferred independently to cells (thick arrows). These two transfers can have occurred either before or after the LUCA. In the first case, the two systems might have been present in LUCA via cell fusion or successive transfers. One system could have also replaced the other in a particular cell lineage (for these different possibilities, see fig.)

![]()

An artist's depiction of gas and dust in the forms planets, surrounding a young star in their orbits. (Image credit: NASA).

�

The solar system is anchored by our Sun. Before the solar system existed, a massive concentration of interstellar gas and dust created a molecular cloud that actually formed the sun's birthplace. Cold temperatures caused the gas to clump together, growing steadily denser. The densest parts of the cloud began to collapse under their own gravity, perhaps with a nudge from a nearby stellar explosion, forming a wealth of young stellar objects known as protostars.

Gravity continued to collapse the material onto the infant solar system, creating a star and a disk of material from which the planets would form. Eventually, the newborn sun encompassed more than 99% of the solar system's mass, according to NASA (opens in new tab). When pressure inside the star grew so powerful that fusion kicked in, turning hydrogen to helium, the star began to blast a stellar wind that helped clear out the debris and stopped it from falling inward.

Although gas and dust shroud young stars in visible wavelengths, infrared telescopes have probed many clouds in the Milky Way galaxy to study the environment of other newborn stars. Scientists have applied what they've seen in other systems to our own star.

![]()

An artist's depiction of gas and dust surrounding a young star. (Image credit: NASA).� The solar system is anchored by our sun. Before the solar system existed, a massive concentration of interstellar gas and dust created a molecular cloud that would form the sun's birthplace. Cold temperatures caused the gas to clump together, growing steadily denser. The densest parts of the cloud began to collapse under their own rotational gravity, perhaps with a nudge from a nearby stellar explosion, forming a wealth of young stellar objects known as protostars.

Gravity continued to collapse the material onto the infant solar system, creating a star and a disk of material from which the planets would form. Eventually, the newborn sun encompassed more than 99% of the solar system's mass, according to NASA(opens in new tab). When pressure inside the star grew so powerful that fusion kicked in, turning hydrogen to helium, the star began to blast a stellar wind that helped clear out the debris and stopped it from falling inward.

Although gas and dust shroud young stars in visible wavelengths, infrared telescopes have probed many clouds in the Milky Way galaxy to study the environment of other newborn stars. Scientists have applied what they've seen in other systems to our own star.

![]()

An artist's depiction of gas and dust surrounding a young star. (Image credit: NASA).� The solar system is anchored by our sun.

Before the solar system existed, a massive concentration of interstellar gas and dust created a molecular cloud that would form the sun's birthplace. Cold temperatures caused the gas to clump together, growing steadily denser. The densest parts of the cloud began to collapse under their own gravity, perhaps with a nudge from a nearby stellar explosion, forming a wealth of young stellar objects known as protostars.

Gravity continued to collapse the material onto the infant solar system, creating a star and a disk of material from which the planets would form. Eventually, the newborn sun encompassed more than 99% of the solar system's mass, according to NASA, (opens in new tab). When pressure inside the star grew so powerful that fusion kicked in, turning hydrogen to helium, the star began to blast a stellar wind that helped clear out the debris and stopped it from falling inward.

Although gas and dust shroud young stars in visible wavelengths, infrared telescopes have probed many clouds in the Milky Way galaxy to study the environment of other newborn stars. Scientists have applied what they've seen in other systems to our own star.

Living - Cell�s planets

����������������������� water-attracting heads of lipid molecules

����������������������������������� water-repellent heads

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One possible family tree of eukaryotes -

Main article: Eukaryote

Chromatin, nucleus, endomembrane system, and mitochondria:]

Eukaryotes may have been present long before the oxygenation of the atmosphere, but most modern eukaryotes require oxygen, which is used by their mitochondria to fuel the production of ATP, the internal energy supply of all known cells. In the 1970s, a vigorous debate concluded that eukaryotes emerged as a result of a sequence of endosymbiosis between prokaryotes. For example: a predatory microorganism invaded a large prokaryote, probably an Archaean, but instead of killing its prey, the attacker took up residence and evolved into mitochondria; one of these chimeras later tried to swallow a photosynthesizing cyanobacterium, but the victim survived inside the attacker and the new combination became the ancestor of Plants; and so on. After each endosymbiosis, the partners eventually eliminated unproductive duplication of genetic functions by re-arranging their genomes, a process which sometimes involved transfer of genes between them. Another hypothesis proposes that mitochondria were originally sulfur- or hydrogen-metabolizing endosymbionts, and became oxygen-consumers later. On the other hand, mitochondria might have been part of eukaryotes' original equipment.

��

There is a debate about when eukaryotes first appeared: the presence of steranes in Australian shales may indicate eukaryotes at 2.7 GA; however, an analysis in 2008 concluded that these chemicals infiltrated the rocks less than 2.2 GA and prove nothing about the origins of eukaryotes. Fossils of the algae-Grypania have been reported in 1.85 billion-year-old rocks (originally dated to 2.1 GA but later revised), indicating that eukaryotes with organelles had already evolved. A diverse collection of fossil algae was found in rocks dated between 1.5 and 1.4 GA. The earliest known fossils of fungi date from 1.43 GA.

CELL_STRUCTURE:

Cell is the unit of structure and function. They are the building blocks of an organism. Irrespective of the nature of organisms (plant or animal) they are either made up of single cell or many cells, the former is called unicellular and later is called multicellular organisms; in the later cells are differentiated into various kinds and they are grouped into tissues, which perform special and special functions.

An Apple with such Sweet Cells.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Example meristematic cells perform repeated cell divisions, phloem cells- conduct food material, sclerenchyma- mechanical support function, xylem- conduction of water and mineral salts and so on. Nevertheless, all these different types of cells are derived from the same embryonic cells. The development of various cell types from a single cell is determined and regulated by a process called differentiation, which in turn is controlled by differential concentrations of plant hormones. Added to this, organ differentiation is another fascinating aspect of development. All these processes are regulated by differential gene regulation in response to environmental stimulus and phytohormones.

Cellular composition:

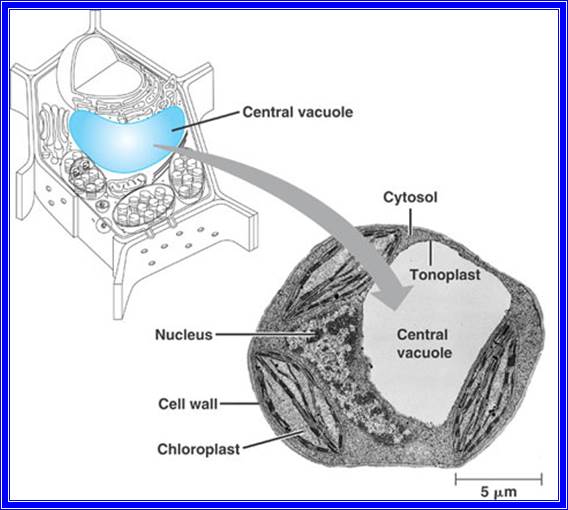

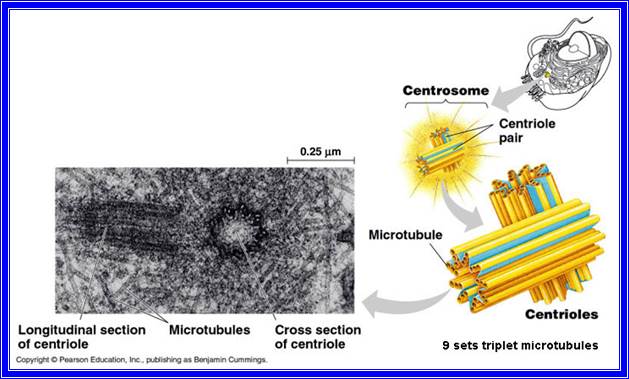

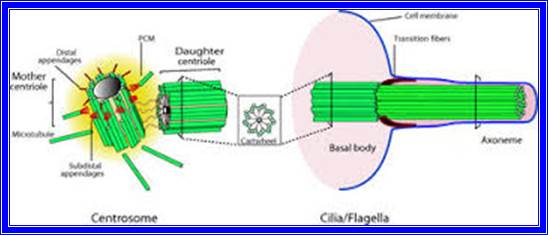

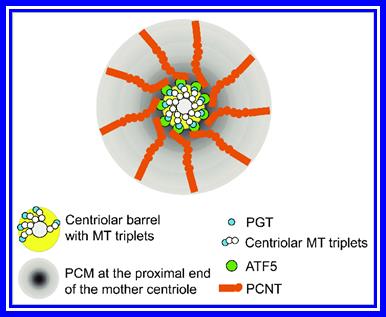

All cells are made up of a semi viscous fluid called protoplasm, which is considered as the physical basis of life, for it controls all biochemical reactions of the cell. In fact, it is the microcosm of life with many secrets not known to us. The protoplasm is colloidal in nature, because many cell colloidal sized structures and macromolecules are suspended in it. It also exhibits sol and gel properties. The granular nature of the protoplasm is due to the presence of many tiny organelles. Vacuoles of various types are also found, but in plant cells when it is matured, a large central vacuole is present and it is separated from the rest of the protoplasm by a single unit membrane called tonoplast. The fluid present is called cell sap. There are many common features between plant and animal cells; the former is distinguished by the presence of distinct cell wall and plastids, which are totally absent in animal cells. However, centrosomes are invariably present in animal cells and rarely in plant cells with exception of some lower plant unicellular algae like Chlamydomonas.

Chemical composition:

When cells are subjected to chemical analysis the following compounds are found (approximate value).

Compound������������������ Animal����������������������� plant cell

Carbohydrates ����������� �������� 20%�������������������� �������� 30%

Proteins ������������������������������ 45%�������������������� �������� 40%

Lipids ��������������������������������� 30%�������������������� �������� 25%

RNA ����������������������������������� 1%��������������������� �������� 0.4%

DNA������������������������������������ 0.2%������������������� �������� 0.4%

Inorganic &������� others������� 3.8%������������������� �������� 3.6%

Carbohydrates:�These are organic compounds consisting of C, H and O. The basic structural components of carbohydrates are monosaccharide sugars consisting of 3 to 7 carbons. Example: Glucose (6c), Fructose (6c), Erythrose (4c), Xylose (5c), etc. such monomers by undergoing polymerization develop into long chained polysaccharides, such as cellulose, cellobioses, starch and glycogen (animal starch). Cellulose is made up of glucose units linked by β1>4 linkages and it is an important component of cell wall. Similarly, starch is also a polymer of α1-4 linked glucose units and it is the main source of energy for all living cells.

Proteins:�proteins are the most important organic components of cells, for they act as structural as well as functional molecules. With out proteins life cannot exist, though DNA is the genetic material it is proteins that make it or break it; DNA is master library with information, that cannot be changed. Proteins are made up of basic building blocks called amino acids. The polymers of amino acid residues are called polypeptides (proteins) which exhibit different structural conformation (shape). The 3-D shapes are specific and characteristic for a particular protein, thus they exhibit specific structure and function. Exemple: contractile proteins (muscles), transport proteins (Hemoglobin), enzyme proteins, hormonal proteins (insulin), antibody proteins IgG etc. Almost all biochemical activities, including growth and development are controlled by proteins, without which cell ceases to live.

Lipids:�Fatty acids and their derivatives are very important for two reasons, firstly lipids like lecithin, phosphotidyl ethanolamine, sphingolipids, glycolipids, steroids and others are part of the cellular membranes; thus, they contribute to the structure of the membranes. Secondly lipids also act as food reserve and provide energy by oxidation.

Nucleic acids:�These are the polymers of nucleotides, consisting of nitrogenous bases, phosphates and pentose sugars. There are two types of nucleic acid � 1) Deoxy-ribose nucleic acid (DNA), 2) Ribose nucleic acid (RNA). DNA is mostly found in chromosomes; it is the repository of genetic information and it provides information for the synthesis of proteins. The chemical composition, structure and function will be discussed in the chapter elsewhere.

Inorganic/Organic factors:�Many inorganic metals Fe, Mg2+, Mn2+, Mo, ca2+ etc. are very important, for they are either the integral part of some organic molecules or act as co-factor in enzymatic activities.

Certain organic factors, important for cellular metabolism, because many of the vitamins act as co-enzymes; these are required for enzymatic activities, without which cellular processes come to stand still.

Size and shape: The size of cells varies from 10 micron to many centimeters in length. For example, cotton fibers are several mm in length. The shape ranges from spherical, isodiametric, and hexagonal to tubular. This is genetically predetermined to perform different functions.

Cell structure:

When the cell is observed through light microscopes, which may have the maximum resolution of about 2000 times, very few details can be made out. On the other hand, if sections of the cells are observed through electron microscope, which has a resolution power ranging from 50,000 to 150,000 times enlargement, even smaller structures stand out clearly. Inspite of high resolution, it is not possible to make out all the structural details.

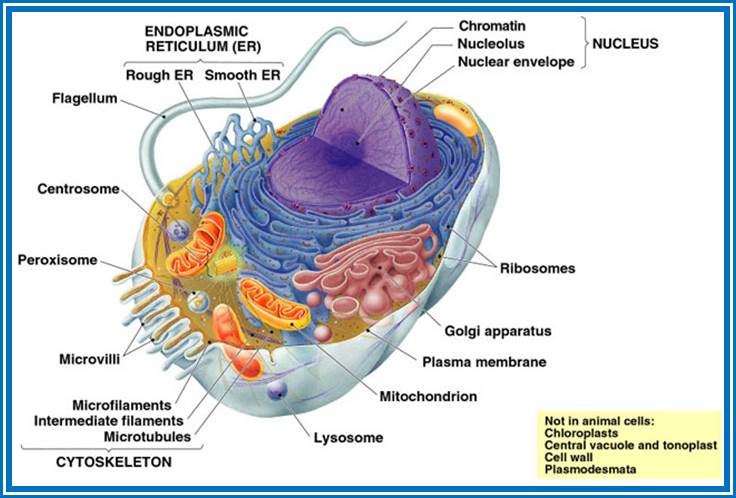

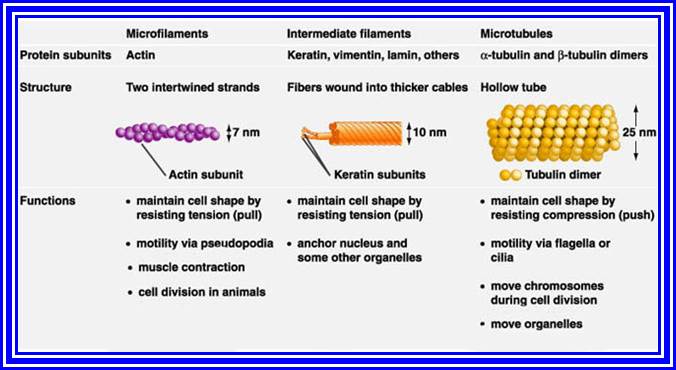

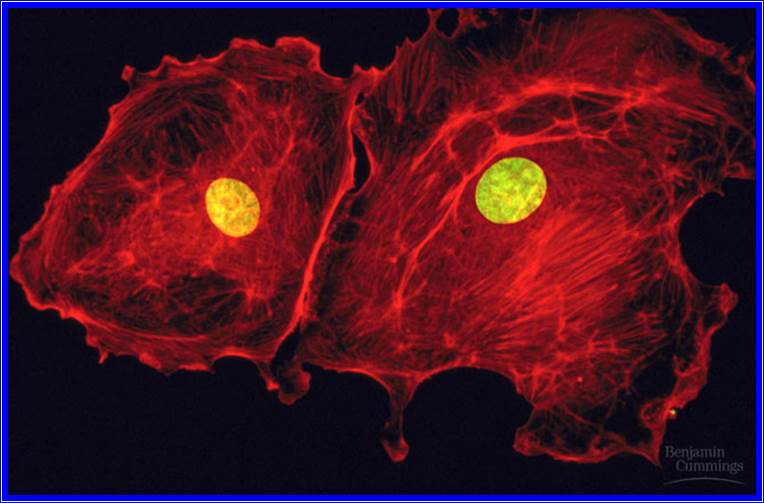

The following structures are found in the cell, 1) Cell wall, 2) Plasma membrane, 3) Nucleus, 4) Plastids, 5) Mitochondria, 6) Golgi complex, 7) Ribosomes, 8) Cytoskeleton, 9) Micro bodies, 10) Centrosomes,11) Endoplasmic reticulum, 12) Central Vacuole and 13) Non-living cell inclusions.

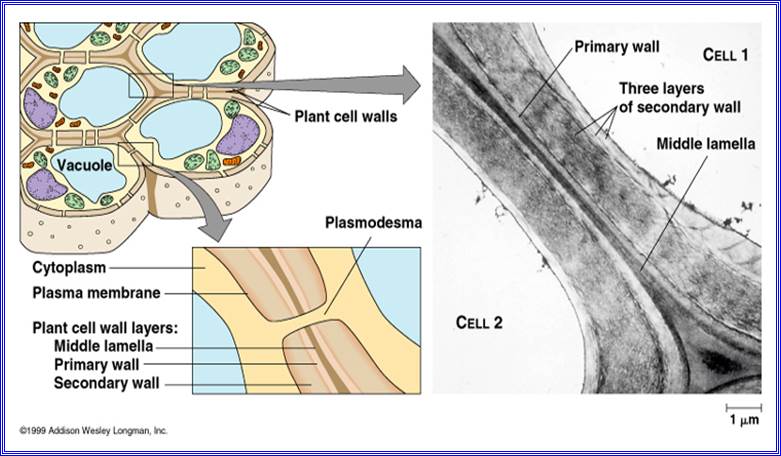

Cell wall:�Only plant cells and bacterial cells posses a protective structure as the cell walls outside the plasma membrane. Bacterial cell wall is firmly adpressed to the underlying plasma membrane.

Its chemical composition and structure are more complex. However, it is basically made up of long polymers of glucosamine (NAG) and muramic acids (NAM), which in turn are cross linked by short-pentamer oligopeptides; thus, they form a mat like structural layers around the plasma membrane. Hundreds of such layers are deposited one above the other to form a very tough wall. Many bacterial cells produce a mucilaginous pectose layers outside the cell wall and this layer is called the capsule. But many bacterial cells do contain another lipid layer studded with proteins, oligosaccharides and glycol and proteoglycans.

![]()

But higher plants have cell walls mainly made up of cellulose fibers. Addition to these, pectin�s, hemicelluloses and lignin are also deposited on primary cellulose layer; the thickening is only at the later stages of development of the cell.

With proper staining, if a group of cells are observed, the cells appear to be held together by a kind of cementing material called middle lamella. It is made up if calcium

pectate. Next to calcium pectate layer, the cell wall that is laid later is differentiated into 2 or 3 distinct layers. They are primary wall, secondary wall and tertiary wall.

The primary wall is the first true cell wall to be deposited and it is purely made up of cellulose. With the development of the cell, the additional layers are deposited, called secondary and tertiary wall layers, like in the case xylem and sclerenchyma. Certain areas in the cell walls remain without thickening and these are called Pit areas, through which fine protoplasmic strands transverse across between two cells and provide a continuum to protoplasm; they are called plasmodesmata.

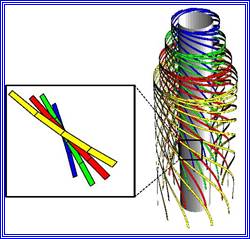

![]()

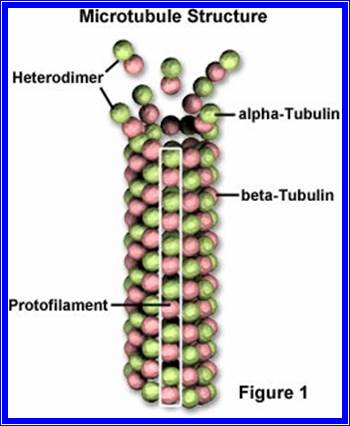

The primary cell wall, which is the first wall layer to be deposited, is made up of cellulose fibres. These fibres are considerably longer and they are deposited layers after layers; oriented longitudinally, transversely or obliquely. The deposition and the orientation of these layers are aided by microtubules that are found on the inner face of the plasma membrane.

Each cellulose fiber is made up of 8000 to 120,800 D- Glucose units, which are linked to each other by glycosidic bonds to form a long chain of glucose units, which show helical conformation. Hundreds of such cellulose threads are grouped into a bundle called micelles; these in turn are aggregated into micro fibrils which by further aggregation develop in to macro fibrils.

Such micro/macro fibrils are deposited regularly either longitudinally or transversely to form uniform layers. These fibres are embedded in a matrix made up of pectate substances and hemi-cellulose materials like poly-xylose and others.

Primary cell wall������������������������� Secondary cell wall

����������������������������������������������������������������������� �

Primarily cellulose����������������������� Few layers of cellulose

Hemicelluloses�������������������������������������� Xylose, mannose

Pectic����������������������������������������������������� Complex lignins

Elastic���������������������������������������������������� Non-elastic

Laid on middle lamellae��������������� �������� Laid over primary wall

1-3 micron thick������������������������������������������������������ >5-10 micron thick

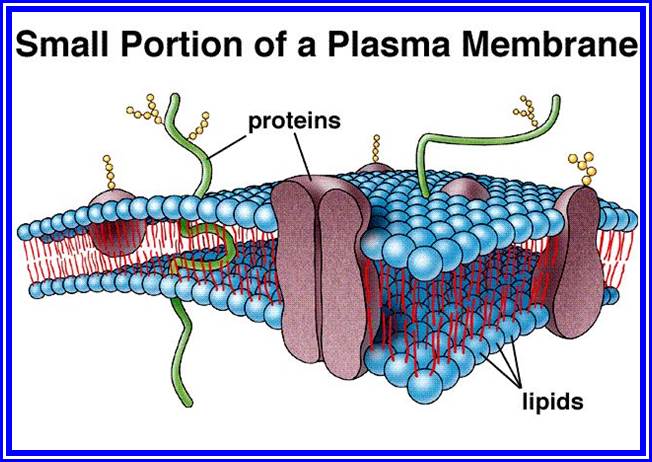

Cell membranes:

These are the most important structures of the cell, for they are responsible for protecting and separating the protoplasm from the external environment.

It helps in selective uptake and transport of ions, provides surface area for many biochemical signal transduction reactions and also helps in specialized functions. In fact, most of the cell organelles are bounded by membranes. Notwithstanding this, a large number of functional molecules are integrated into these membranes.

Chemical composition:

Almost all membranes are basically made up of proteins and lipids. The ratio between proteins and lipids may vary in different cell membranes, but generally it is equal. It is not uncommon to see some carbohydrates as glycoproteins associated with membrane on the outer surface of plasma membranes. Proteins found in membrane are not of the same kind, but differ in their structure, chemical composition and function. Some of them are large and many of them may be smaller. However, most of the proteins are globular in nature having either hydrophilic or hydrophobic or both the characters. Lipids, on the other hand are of various kinds. The common lipids found in the membranes are phosphatidyl choline (Lecithin), phosphatidyl ethanolamine, Phospholipids glycerol, cholesterol, etc. some of the phospholipids exhibit hydrophilic groups at one end and hydrophobic at the other end. Nevertheless; the composition of lipids varies from membrane to membrane, for they have different functions to perform.

Membrane structure

The structural organization of various compounds with in the membrane was an enigma for a long time. With the advancement of biological techniques, it has been found that the membranes exhibit fluid-mosaic structure (Singer and Nicholson 1972). Basically, lipids form bilayers by organizing hydrophobic layers facing each other and the charged region outer surface. Proteins, depending upon the charged nature, some are found on the surface and some are embedded. But proteins & lipids of various kinds are oriented towards each other in such a way, they exhibit semi-solid (crystalline) and semi fluid properties. The arrangement of lipids and proteins is of mosaic pattern, where many proteins are half buried in the lipid bilayers and some traverse the entire cross section of the lipid layer in such a way a part it is buried in the core and some are located at the peripheral surface. The structural and chemical heterogeneity is the hall mark of these membrane structures. This model explains various biological phenomena observed in most of the biological systems.

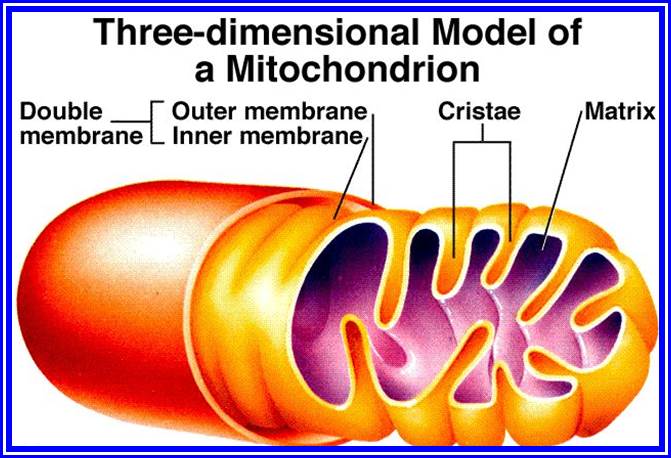

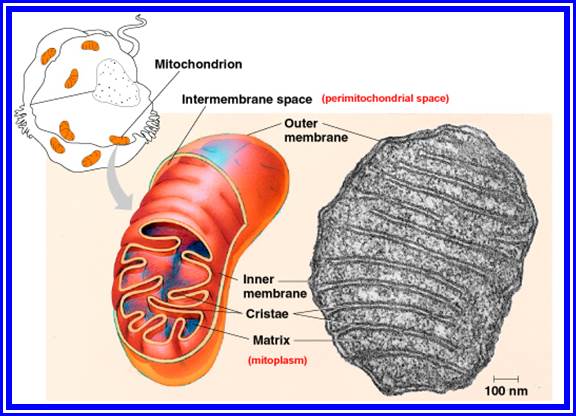

Various types of membranes found in the cell, like plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum; organelle membranes exhibit basically the same structural pattern, but vary in their lipid and protein composition. Some of them are single unit membranes (plasma membrane, tonoplast, Lysosomes and peroxisomes) and some have double membrane systems (endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear membrane, golgi membranes chloroplast membrane and mitochondrial membrane). However, they show differences in their chemical composition structural features and functions.

Plasma membrane

This is the outer most membrane of the cell, within which all protoplasmic structures are included. In plants, cell wall acts as an additional protective layer on the outer surface of PM, but in animal cell, plasma membrane itself is the bounding membrane.

This membrane is on the inner surface of the cell wall and performs various functions like osmosis, selective absorption of various mineral nutrients, accommodates innumerable signal transducing receptors for various stimuli (electrical, light mechanical and chemical) and invariably exhibits dynamic properties. Proteins found in the plasma membrane are vectorial (directional) arranged. At some places, the plasma membrane shows inward projections and they are in continuity with the endoplasmic reticulum. Plasma membrane is also the site for pinocytosis and phagocytosis. Thus, the plasma membrane exhibits unique but varied properties of its own. It exhibits dynamic fluidity never to be constant and stagnant.

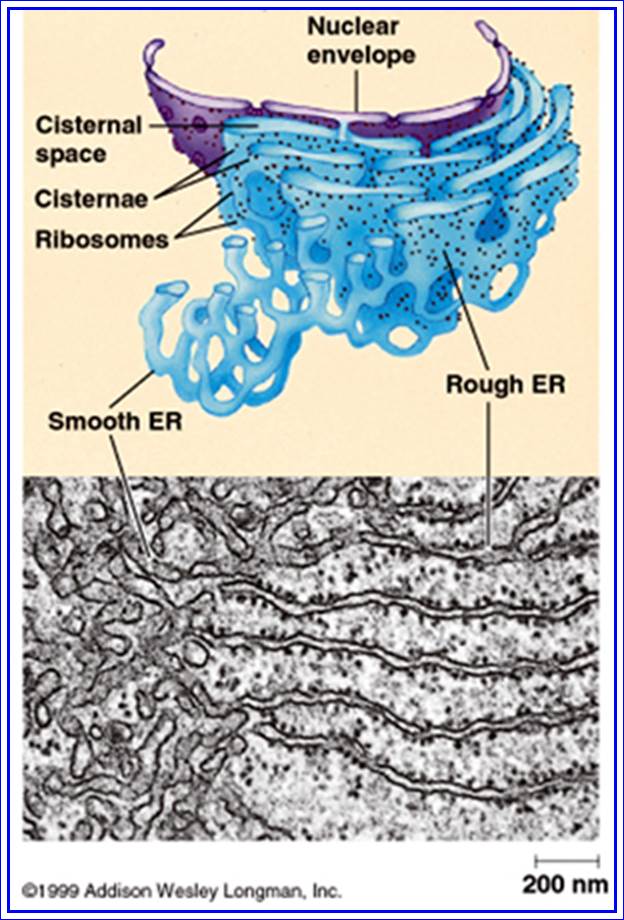

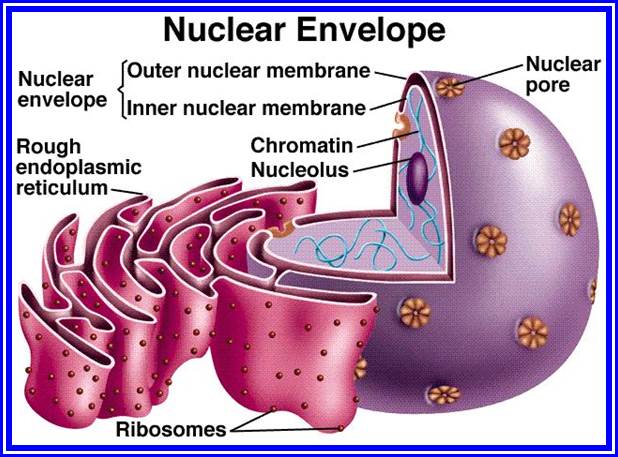

Endoplasmic Reticulum:

It is a labyrinthine net work of double membrane sheets. They are found in all living cells with the exceptions of mature erythrocytes and cells of bacteria. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) occupies more than 50 to 90% of total cell volume. It is in contact with the outer plasma lemma and the outer nuclear membrane. ER is made up of two single unit membranes folded to form adpressed sheets, which enclose a channel or cisternae. ER is extensively branched, thus the surface area for reactions is enormously increased.

�

On the basis of presence or absence of ribosomes on the surface, two classes of ER can be recognized.

�

1) Smooth ER (SER) is without ribosomes, 2) Rough ER (RER) has innumerable ribosomes on its outer surface. These membranes are highly mobile and they undergo rapid flux, changing from SER to RER and RER to SER. Added to this, the entire ER exhibit continuous sweeping movements which help in the distribution of cellular components in the matrix. The ER membranes are supported by microtubule skeletal network. These membranes are highly dynamic and show rapid turnover.

Functionally ER exhibits various activities like synthesis of proteins, mechanical support for the fluid protoplasm, synthesis and storage of lipids, synthesis and storage and transport of proteins to different destination through golgi membranes. Some of the functions are detoxification, transport of various cellular components, formation of micro bodies, formation of secretory vesicles, cell plate and others. The above-mentioned functions indicate that the ER is at the heart of various cellular activities. Furthermore, during the development of nucleus and other cell organelles like, chloroplast, mitochondria, golgi complex, micro bodies, Lysosomes etc. ER provides membrane fractions to them. Exchange of membrane components among them is pervasive and common.

Golgi bodies

![]() A group of membrane cisternae, discovered by Camillo Golgi

in 1890, are called as Golgi bodies. They are present in all cells except

bacterial and blue-green algal

A group of membrane cisternae, discovered by Camillo Golgi

in 1890, are called as Golgi bodies. They are present in all cells except

bacterial and blue-green algal ![]() cells.

These structures vary in number from cell type to cell type. In secretory

tissues like thyroid and liver they are present in large numbers than in other

type of cells. They are abundant in secretory surfaces like stigma of the

pistils.

cells.

These structures vary in number from cell type to cell type. In secretory

tissues like thyroid and liver they are present in large numbers than in other

type of cells. They are abundant in secretory surfaces like stigma of the

pistils.

����������������������������������� Electronic-Micrography

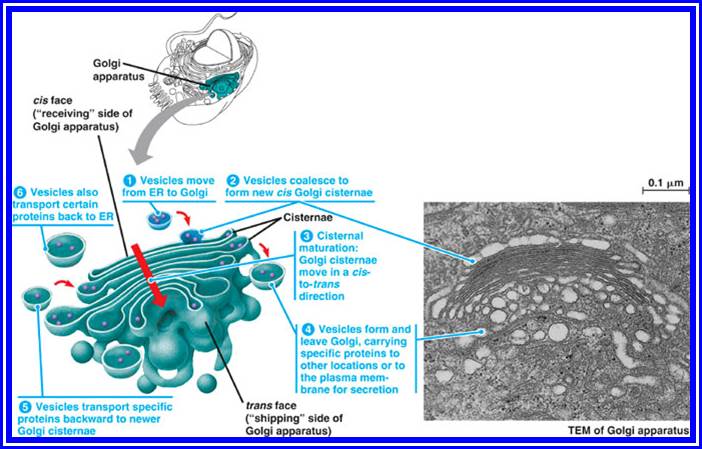

Golgi bodies are made up of a group of stacked membrane cisternae. Some times these membranes structures show extensive reticular network. Generally, the distal ends of double membranes are dilated into vesicles and some of the vesicles are in the process of pinching off. An interesting feature is that the Golgi complex is surrounded by ER and at some places they look like in continuity with ER, but these proximal membranes of ER are free from ribosomes called SER (smooth ER).

The stacked Golgi membranes have two faces, i.e., formation face is called cis face and maturation face as trans face. The formation face has convex surface and has a number of small vesicles pinched off from SER. In fact, certain proteins synthesized on the RER, enter into the lumen of ER and hence they are transported in the lumen towards the transitional ER which are in close association with Golgi complex and then the protein containing ER membranes pinch off as vesicles. These in turn fuse with one another or with golgi cis membranes and develop into membranous sacs. Within these membranous sacs, proteins and such products get further modified. Later such products are sorted out and get enclosed and pinched off in the form of vesicles from maturation face called Trans surface of the Golgi complex.� Similarly, many secretary products that are synthesized on RER and transported into Golgi complex, later the matured products get enclosed in vesicles and budded off.� ��The golgi derived vesicles are loaded with proteins that are specifically targeted to various destinations.

Thus, Golgi bodies perform various complex processes, like glycosylation of proteins, synthesis of cell wall polysaccharides, maturation of zymogen granules, formation of primary lysosomes, secretion of lipid bodies, acrosome formation, neural secretion etc.� Nevertheless, the participation of ER is every essential in the function of Golgi membranes.� Golgi membranes are associated with transport of proteins from one site to the other. In all the above-mentioned processes, packing, maturation and secretion of specific substances are the most important events of Golgi functions. �The golgi complex is at the heart of membrane flow.

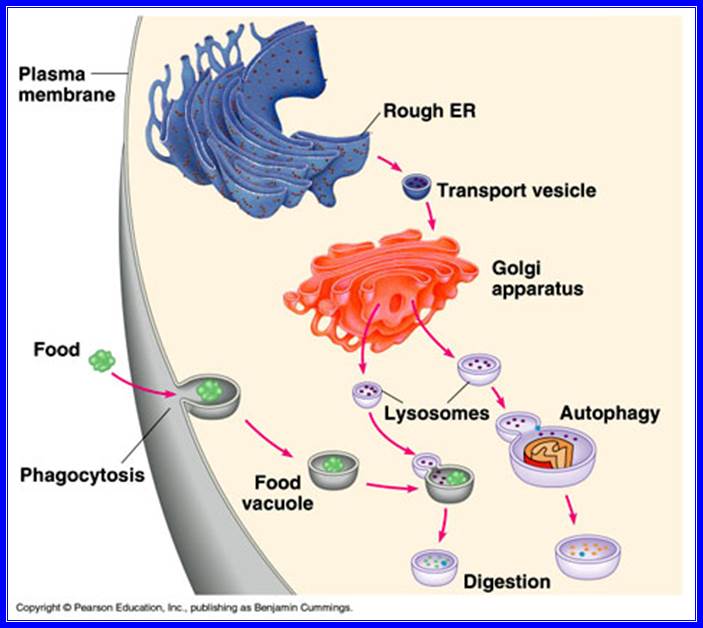

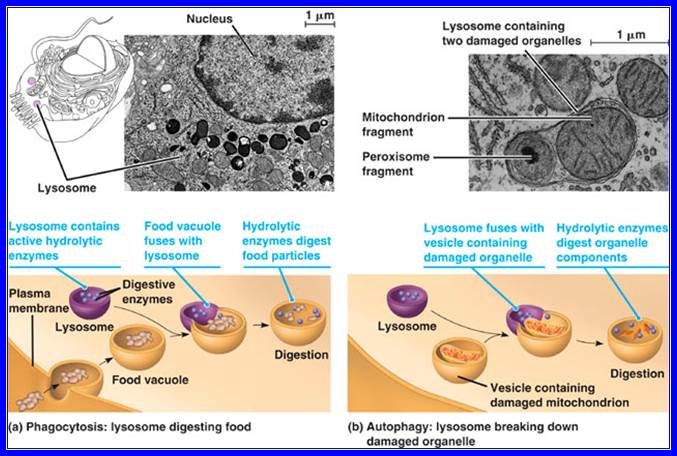

Lysosomes:

Though these organelles were noticed in 1949, later it was de Duve who coined the term Lysosomes for such dense bodies.� Lysosomes are often called suicidal bags, misnomer, for they are capable of digesting various cellular structures and digest every food etc., if they are damaged and make to break open to release the contents.

Phagocytosis and Autophagy

Phagocytosis and Autophagy

Without any exception, all eukaryotic organisms contain these organelles in their cells.� These are found in various sizes.� Lysosomes are bounded by a single unit membrane and enclose a group of hydrolytic enzymes.� Paradoxically, the surrounding membrane is not digested by the enclosed hydrolytic enzyme; this is probably due to special modifications of the membrane and lysosomal fluid which is more acidic.� The intactness of the membranes is mainly dependent upon certain membrane stabilizers like cholesterol, cortisones, cortisols, vitamin E, antihistamines, heparin etc.� On the other hand, substances like Vitamin A, Vitamin B, Vitamin K, B-estradiol, testosterone and digitonin labalize and cause leakiness.� Sometimes at higher doses, the membrane may completely disperse and all the lysosomal contents may be released.� As a result, the cell may be completely digested.

Lysosomes are important cell organelles in digesting various macromolecules like carbohydrates, proteins, fats, DNA, RNA and others.� The breakdown of these molecules during various stages of development and metabolism is governed by the controlled release of these enzymes.

The origin and development of lysosome itself is controlled by many environmental factors.� For example, when an organism is starved of food, lysosomal number increases tremendously.� This is in order to degrade whatever food material that is available in the cell. Similarly, when yeast cells are subjected to anaerobic conditions or starved of food, within minutes, Lysosomes increase in number and actively; they chew up all the available materials including mitochondria.� In the case of germinating castor seeds or maize grains the increased lysosomal activity helps in the degradation of fats and starch into simple molecules for the growing seedlings.� The number of enzymes and the kinds of enzymes found in each of lysosomes is not same or constant.� The contents vary depending upon the tissue and the metabolic status of that tissue.� Commonly available lysosomal enzymes are nucleases, phosphotases, lipases, proteases, glycosidases and sulfatases.� Even some of the condemned proteins are taken in through L.AmP proteins on its membrane surface and digest the same. Many of the lysosomal enzymes are released in a regulated way and they have definite pH optima for their peak activity. Lysosomes and some trans golgi vesicles and incoming endosomes form a kind of network which provide material for its growth and maintenance.

Curiously enough, lysosomes take their origin from Golgi bodies.� Lysosomes enzymes are synthesized on RER: then they are transported to smooth transitional vesicles.� Afterwards they are integrated into Golgi sacs at the formation face.� After undergoing modifications and packing, they are then sorted into vesicles, which are budded off from maturation-face of the Golgi complex.� The vesicles containing lysosomal enzyme are marked by the addition mannose6-phosphate, such vesicles ultimately dock with lysosomes via late endosomes or directly.� These may further fuse with one another to form larger structures or they may fuse endosomes or and with phagocytotic vesicles (phagosomes) to form secondary lysosomes, where the engulfed substances are digested and the products are resorbed into cytoplasm.� The undigested materials are removed by defecation.� Many a times, the lysosomes move towards the plasma membrane and unload all their contents, thus they cause extracellular digestion.� Lysosomes also play a significant role in the acrosome formation (cap structure) of spermatozoid. The presence of such cap structures in sperms help in their penetration through the tough cortical walls of the egg cells.

Lysosomes are also known to play a very important role in metamorphosis of amphibians and insects.� For example, during the transformation of tadpole into adult frog; the long tail of the tadpole gets digested by the lysosomal activity, the process called resorption.� Recent investigations have further shown, that the increased activity of lysosomes causes severe destruction of tissues, probably of lysosomes cause severe destruction of tissues, probable break down of chromosomes leading to abnormality; perhaps even cancer may be induced.� Another instance of lysosome induced disease is Rheumatoid arthritis (Joint pain).� Thus, lysosomes play a significant role in the metabolism and development of an organism. One can also find various lysosomal based human diseases.

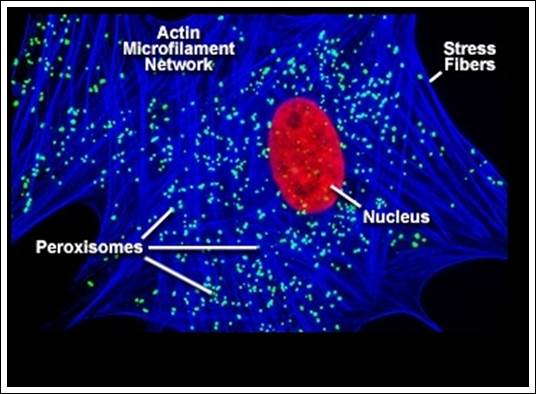

Microbodies;

These are spherical, electron dense, granular bodies.� They are bounded by a single unit membrane.� Such structures are found in both animal and plant cells.� Their number varies from 50 to 100 per cell; their number can increase or decrease based on the requirement.� Germinating seed cells show maximum numbers; often they form a link between chloroplast and mitochondria, where peroxisomes are involved in the detoxification of oxygen free radicals by catalase or peroxidase activity.

There are two types of micro bodies and they are characterized by their functions viz., 1) peroxisome, 2) glyoxysomes; the former exhibit peroxidase activity and the later show glyoxalate activity.� Such bodies are found in various tissues like liver, kidney, intestine, brain, lung epithelial cell, testis, brain, adipose, and photosynthetic cells of green plants.

In C3 plant cells (Calvin plants) they are closely associated with mitochondria and chloroplasts.� They are responsible for photorespiration.� This process severely results in the depletion of photosynthetic products.� However, they are not that active in C4 plants.� Nevertheless, in C3 plants both Glyoxysomes and Peroxisome act co-operatively utilizing Ru-DP glyoxalate and breaking it down to glycollate, which is then metabolized by peroxisome.� On the other hand, in animal tissues like liver and other cells, various substances like urea, amino acids, lactic acid etc. are oxidized by peroxisome to H2O2.� In this process oxygen is utilized.� As H2O2 as peroxide is fatal to living cells, it is salvaged or removed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) reaction and oxidation to water by utilizing substrates like ethyl alcohol, methyl alcohol, nitrates, etc.� The presence of these structures and their function is fascinating, for their exact role is not clearly understood.� They are also implicated in thermoregulation of certain organisms.

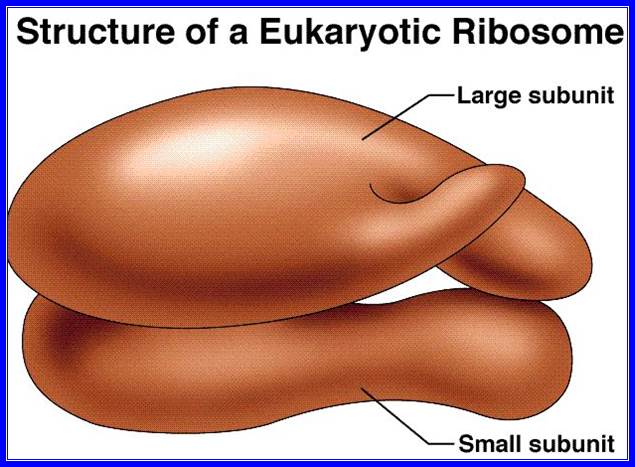

Ribosomes:

Ribosomes are ultramicroscopic cellular organelles, first observed by Palade.� Though they are submicroscopic in size, they are extremely important, for they are responsible for the synthesis of proteins.

Ribosomes are found in millions, in eukaryotic cytoplasm, but in bacteria, ribosomal count is approx. 20000. �They are also found in organelles like chloroplasts and mitochondria.� These structures are either roughly spherical or ovoid in shape.� They are very stable and can remain functional at least 120 days or so.� Basing on the molecular weight (determined by equilibrium density ultra centrifugation) they have been broadly classified into two types, i.e., 80S and 70S types. The S-values of the slightly vary among the organelle ribosomes. Ribosomes of 80s type are exclusively found in eukaryotic organisms.

�

�������� Structurally both 70S and 80S ribosome look alike.

But 70s ribosomes are restricted to prokaryotic organisms like bacteria and blue-green algae.� Still smaller ribosomes are found in mitochondria and chloroplasts, but their sizes vary.

When functional ribosomes are subjected to Mg2+ depletion, they separate into large and small subunits.� If the concentration of Mg2+ is increased the free subunits reassemble into functional units.� The concentration of Mg2+, if further increased, ribosomes aggregate into dimmers, tetramers or octamers, thus one can precipitate ribosomes and collect them by centrifugation.�

The smaller subunit under electron microscope exhibits a shape of elongated cucumber with an indentation and a twist.� But the larger subunit shows a shape of a mother in sitting position with the knees upright, having the baby on her lap.� Here the �Baby� is equivalent to a smaller submit (note this purely my imaginary explanation not found in any text books).� The larger subunit has a grove in the middle through which the nascent polypeptide traverses and exits.

Ribosomes found in the cytoplasm exist either in membrane bound state or free state.� The ratio between these varies from cell to cell type and depends upon the functional state of the cell.� But in bacteria most of the ribosomes exist in free state.

Chemical analysis of these structures indicates that they are made up of proteins and ribose nucleic acids (rRNA) roughly in equal ratios.� The proteins of larger subunit of prokaryotic bacteria consist of 34 subunits called L1 to L34 and the smaller subunit has 21 factions, s1 to s21.� Each one of these proteins is unique with the exception of two proteins i.e., S 20 and S 26 which are present in both the ribosomal units.

Ribosomal RNA exists in three or four different sizes which are expressed in Svedberg units (S) as shown in the table below.

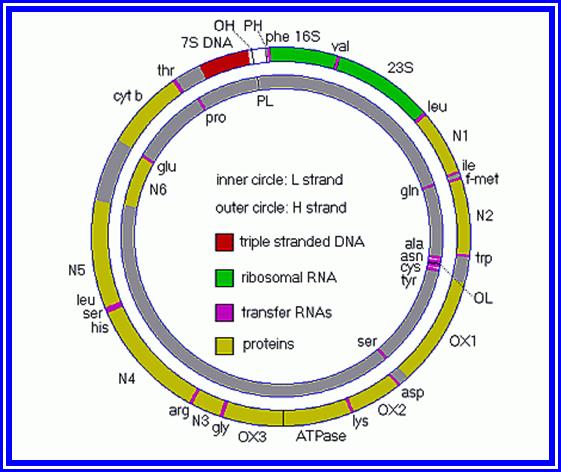

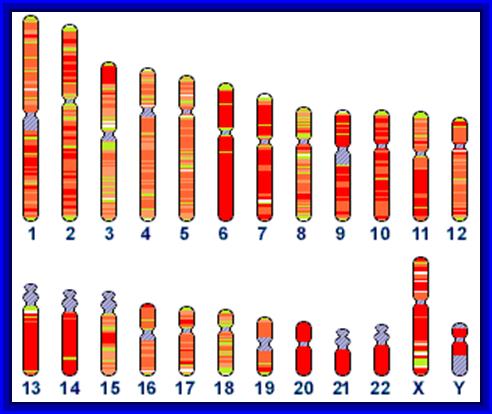

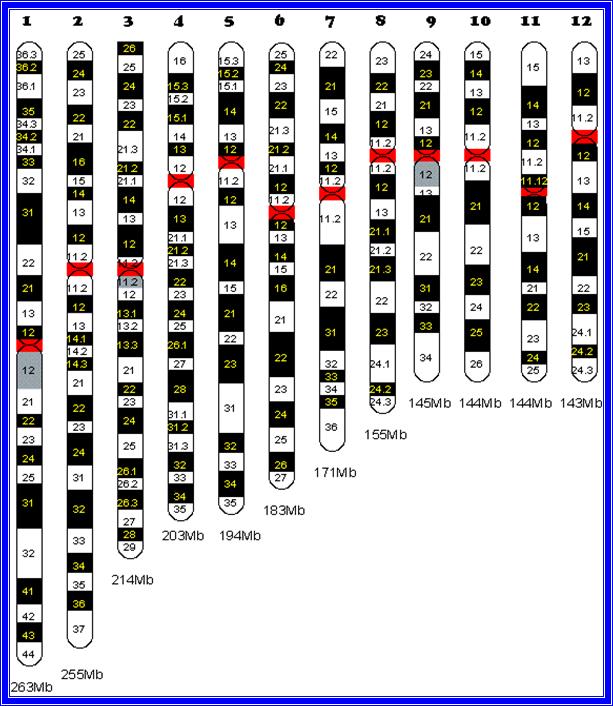

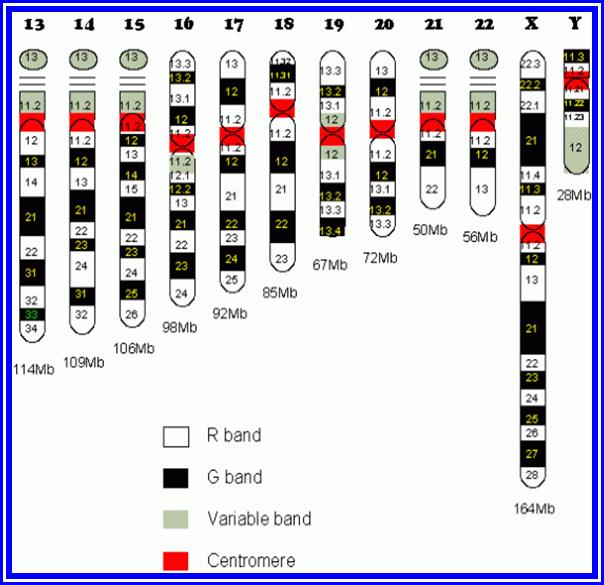

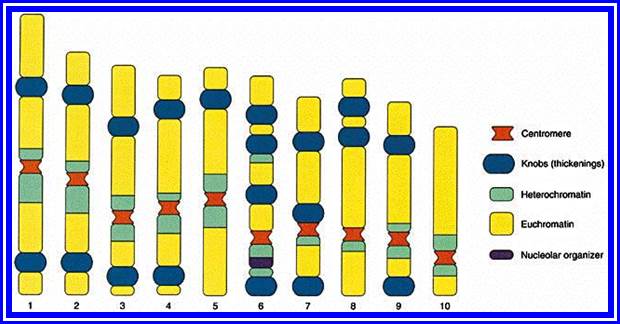

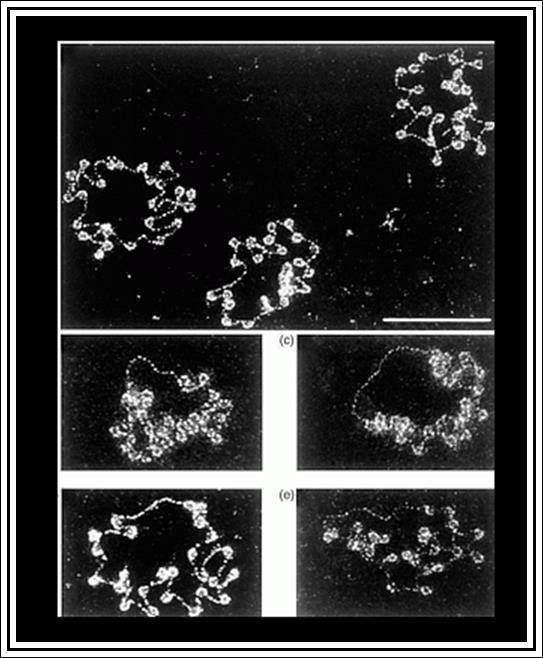

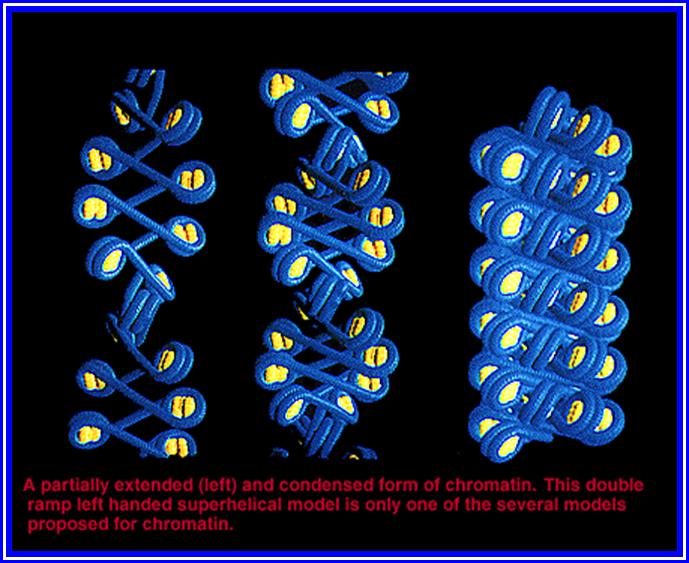

The RNAs present in ribosomes show various sizes, and most of them are rich in Guanosine and Cytosine nucleotides.� In prokaryotes rRNAs coded for by seven operons as precursor containing 16s, 23s and 5s RNA.� Such precursors also contain tRNA blocks tucked in them. The genes responsible for the synthesis in eukaryotic cells are found in multiple copies ie. of 200-500 organized in tandem repeats. �Furthermore, rRNA genes are exclusively found in secondary constrictions or nucleolar organizer region of the chromosomes, in humans they are located on chromosomes 13, 14, 15 21 and 22. The rRNA genes contain 28S RNA, 5.8sRNA and 28sRNA gene, but the 5 S RNA genes are found elsewhere and spread over in other chromosomes.� These RNAs are transcribed on rRNA genes as larger precursor molecules (45S RNA) and then they are spliced and processed into smaller molecules such as 28 S, 18 S and 5.8 S RNAs. Notwithstanding this, the ribosomal RNA genes in the case of Frog oocytes are amplified 1000-fold.� Enormous number of ribosomes are synthesized and accumulated in the eggs.� Another interesting aspect of ribosomes is that, various ribosomes proteins are coded for by the chromosomal DNA other than the nucleolar DNA.� They are synthesized in cytoplasm and they are transported into nucleolar region of the nucleus.� There, the rRNA and ribosomal proteins associate to form functional subunits of ribosomes in a hierarchical fashion. Later they are transported to cytoplasm through nuclear pore complexes to perform protein synthesis.

However, mitochondria and chloroplast employ a different mechanism for the assembly of ribosomal components. Organelles synthesize their own rRNAs and get imported riboproteins from cytoplasm and assemble functional ribosomes which more or less similar to prokaryotic ribosomes in size and function.� Their activity can be inhibited by chloramphenicol.

The quintessential function of ribosomes is to act as dynamic machinery for the synthesis of proteins.� This is achieved by the association of ribosomes with messenger RNA (m.RNA) and amino acid loaded transfer RNAs (aat.RNA).� Many ribosomes may be associated with a single m.RNA and such a cluster is called polysome.� These polysomes may be free from membrane, or membrane bound.

Plastids:

Plastids are very important cell organelles found mostly in plant cells. They are mainly responsible for photosynthesis.

�

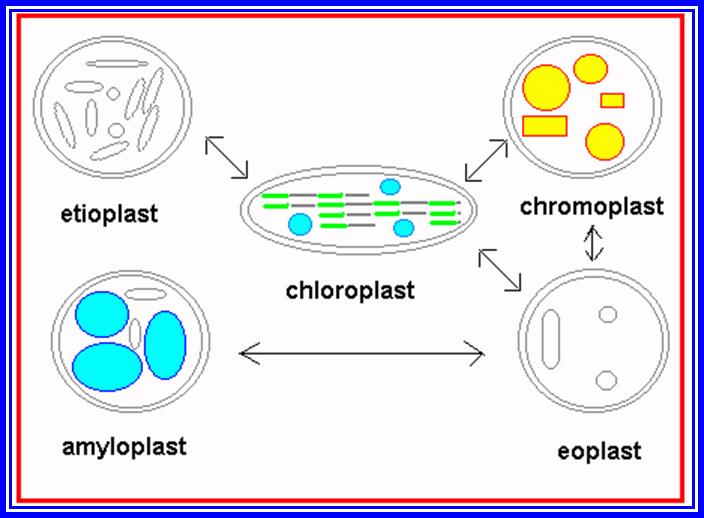

Proplastids to different Plastid�s forms.

Green color of plants is due to the presence of green pigments in plastids. Other colors found in various structures like leaf and flowers are due to the presence of other colored pigments in the plastids (other than green).� Basing on the presence or absence of pigments, plastids have been broadly classified into colorless plastids (Leucoplasts) and color plastids (Chromoplasts).� If the plant tissue containing Leucoplasts are exposed to sunlight, they may turn into chromoplasts.� On the contrary, if plants with chromoplasts are kept in dark for sufficient time, the chromoplasts will be transformed into colorless plastids.

Leucoplasts are generally found in roots and inner tissues, which do not receive sunlight.� Such plastids normally store different kinds of food materials like starch, proteins and oils; basing on this they are called Amyloplasts (store starch), Proteinoplasts (proteins) and Elaioplasts (oil).� Such structures are also found in abundance in various storage organs like fruits, tubers and oil seeds.

Chromoplasts, on the other hand depending upon the dominant pigments present, are classified into chloroplasts (green) Rhodoplasts (Red), Fucoplasts (brown), Xanthoplasts (Yellow) and so on.� Majority of terrestrial plants and aquatic plants like green algae contain chloroplasts.� It is important to note that plants found in ocean which account for the major part of vegetation on this planet, contain different kinds of chromoplasts and also green plastids.� While eukaryotic plants (higher plants) contain well developed plastids, plants like photosynthetic bacteria and blue green algae (prokaryotic) do not possess such plastids, but still they perform photosynthetic functions because the photosynthetic pigments are either found organized in the form of stacks of membranes or as vesicular structures called chromatophores.

Number:� The number of plastids, particularly in green plants, varies from one to hundred or more.� Plants like Chlamydomonas have only one chloroplast; spirogyra has two spirally coiled chloroplasts and in higher green plants like angiosperms the number varies from 20 to 100 per cell.

Shape:� Chloroplasts show some interesting variation in their shape.� This shape is constant for a given species.� For example in Chlamydomonas, it is cup shaped; in spirogyra it is spirally coiled and ribbon shaped, in Zygnema it is star shaped, in Hydrodictyon it is reticulate type and in higher plants it is oval or spherical. Shape and size of chloroplasts is species specific.

Size:� It varies from 0.5 micron to 6 micron in diameter but again its fully formed has specific sizes and species specific.���

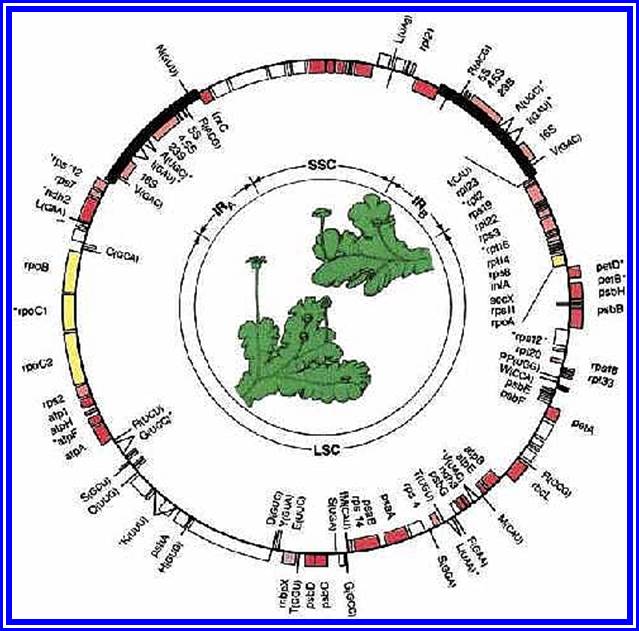

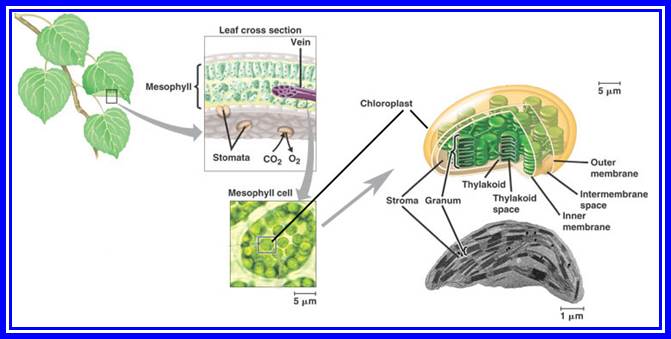

Structure:� Basically, most of the chloroplasts are bounded by two single unit membranes and the space between them is called periplastid space.� Inside the membrane system, chloroplasts are filled with a highly complex fluid called stromatal matrix or simply called stroma.� Within this fluid, various specialized structures, macro molecules and enzymes are either suspended state or the fluid shows flux.� The structures found are grana, ribosomes, DNA, RNAs, starch and other various enzymes, coenzymes required for carbohydrate and fatty acid synthesis and amino acids.

Grana:� These are the most specialized membrane systems derived from the inner chloroplast membrane. A single chloroplast may contain 10-30 grana. �Each granum is made up of 10-60 circular membranous discs stacked one above the other and such discs are called thylakoids.� The grana are inter-connected by the thylakoid membranous extensions called inter-granal lamellae or stromal lamellae.� However, in C4 plants, like sorghum, sugarcane and other tropical grass plants, chloroplasts show two types of organizations, i.e., the chloroplasts found in the bundle sheath cells do not possess any differentiated granal structures, but are filled with diffused stromal membranes, arranged parallel.� However, chloroplasts found in mesophyll cells show granal structures. �Chloroplasts in bundle sheath show centrifugal arrangement, i.e., chloroplasts are oriented towards the mesophyll cells.� Protoplasmic connection is found between mesophyll cells and bundle sheath cells.

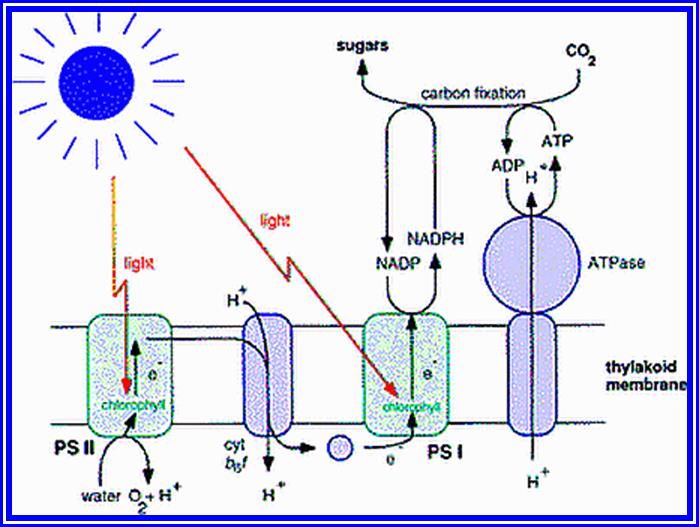

Thylakoid:�Thylakoids are the highly differentiated and say, super specialized circular membranous cisternae, in which various molecular complexes are embedded and they are responsible for photochemical reactions.� Though the membrane has the same basic components and organization as that of any other unit membrane, it is the assembly of photosynthetic pigments and its associated proteins makes it a specialized membrane system.� But photosynthetic pigments like, Chlorophyll-a Chlorophyll-b, Carotenoids and their associated proteins are grouped in such a way that they act as units for performing photosynthetic functions.� Based on the chemical composition, size, structure and function, they are classified into Photosystem I and Photosystem II.� Each of these photosynthetic units contain about 250-300 chlorophyll molecules associated with specific and specialized proteins.� These photosystems appear to be granular in structure of different dimensions.

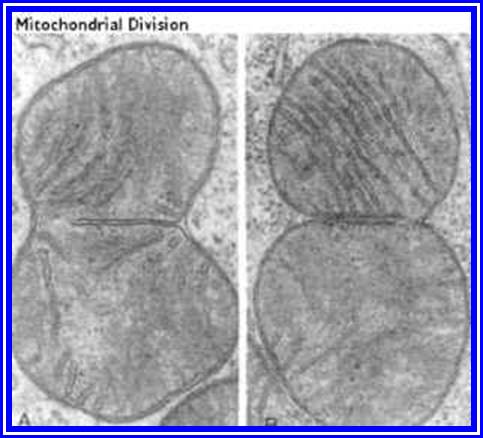

If thylakoid membranes are cut open by freeze-fracture method and observed under electron microscope they reveal the presence of two types of photosynthetic units of different dimensions and they are called Quantasomes The larger quantasome, which is found on the inner surface has a size of 185A^o. �They are grouped into an array of 4 to 6 units.� On the other hand, the smaller particles are of 110 A0 size and are found arranged on the outer surface of the membrane.� The former particle has been identified as photo system II and the later as photo system I.� The outer surface of the thylakoid membrane i.e. surface A is also studded with granular particles of different sizes.� They have been identified as RuBP carboxylase and ATP synthetase units.� However, PS I and PS II are arranged in such a way they fit into one another like Jig-saw structures.� This �close and tight� fit arrangement helps in the co-coordinated functioning of the photosystems.� But the inter-granal lamella contain only PS I.� The chemical composition of PS I and PS II and their function is discussed in greater detail in the chapter photosynthesis. �There is another important complex called Cytochrome b6-f complex which acts between these two systems and it is found both in stromal and thylakoid membranes.